|

Parents and teachers often wonder how they can tell if children have a learning disability. There are many different kinds of learning disabilities, but today’s blog post will focus on dyslexia.

While it takes a professional to diagnose a learning disability such as dyslexia, it can be helpful for parents or teachers to look for the indicators. Even preschoolers may exhibit some signs. Perhaps they can’t remember simple nursery rhymes or other rhyming words. Or they may have difficulty recalling the alphabet or identifying letter names, or both, often even the letters in their own names. Some children with dyslexia mispronounce words when speaking that other children their age can say correctly. Once letter sounds are introduced, usually in kindergarten if not earlier, it may be difficult for children with dyslexia to remember the sounds or to associate them with the correct letter names. When reading instruction begins, they may not be able to sound out even basic consonant-vowel-consonant words such as hat or sit. Many do not understand that spoken words are made up of individual sounds—in other words that these sounds can be taken apart or put together (a lack of phonemic awareness). When they attempt to read, they often guess at words rather than sounding them out, or they substitute words with similar meanings, such as kitty for cat. By second grade, children with dyslexia continue to have difficulty acquiring reading skills. They usually require a lot of repetition during instruction, and reading is slow and dysfluent. Because most children with dyslexia have not been able to master letter-sound correspondences (sounding out words), they guess at words when reading and, when possible, often totally avoid reading out loud. Some have word retrieval issues and use general words instead, such as “stuff” or “thing.” Many mispronounce long words—for example, ambliance for ambulance, amulium for aluminum. By second or third grade you may also begin to see students struggling in school. They do not finish tests on time because of their poor reading ability, and spelling has begun to be a problem. Handwriting is often illegible. Children at this age start to realize that they’re different from their peers, and self-esteem may suffer. As children with dyslexia progress through the grades, their reading skills continue to deteriorate unless they receive an appropriate intervention. Any gains that they make do not compare to the gains of their same-age peers. What is worse, their poor reading skills start to affect performance in other subjects. Moreover, when reading is such a chore, these children rarely read for pleasure, and consequently their store of word meanings is limited. Sadly, they often begin to believe that they’re dumb. To save face, they may do whatever they can to avoid reading and sometimes begin to act out in class--or conversely to withdraw. Sometimes teachers and even parents mistake their difficulties for lack of effort and compound the problem by calling them lazy or unmotivated. By about fourth grade, when content area instruction is stressed so much more than it was in the primary grades, children with dyslexia really falter because they are unable to use their reading skills to learn the content. They fall further and further behind. What began in preschool as a minor difficulty snowballs with each grade until the student with dyslexia cannot manage in school anymore without assistance. All subjects are affected, and self-esteem comes crashing down. Although intervention is best in the primary grades, it is never too late. However, the intervention must include intensive reading and writing instruction. Classroom accommodations alone are necessary but not sufficient.

0 Comments

You may suspect that your child has a learning disability, but you want to have it confirmed by an expert. Or maybe you already have a diagnosis and want a second opinion. But first, what exactly is a learning disability?

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), the federal law that governs special education, designates 13 categories of disability. Presented alphabetically, they are: Autism, Deaf-blindness, Deafness, Emotional Disturbance, Hearing Impairment, Intellectual Disability, Multiple Disabilities, Orthopedic Impairment, Other Health Impairment, Specific Learning Disability, Speech or Language Impairment, Traumatic Brain Injury, and Visual Impairment. Specific Learning Disability, the focus of this blog post, is defined as a “disorder in one or more of the basic psychological processes involved in understanding or in using spoken or written language.” This may interfere with:

Note that to be covered by special education, school performance must be “adversely affected.” In other words, it is not sufficient to merely match behaviors to a category’s descriptors; it must be shown that these have a negative impact on school performance, and to what extent. Moreover, there are exclusionary factors; according to the law, a learning problem is not considered a disability if it results primarily from a visual, hearing, or motor disability; mental retardation; emotional disturbance; or environmental, cultural, or economic disadvantage. For instance, a child who is having difficulty reading primarily because of an inability to see the print does not have a learning disability. Similarly, if a student hasn’t been exposed to appropriate instruction, his or her difficulty is not considered to be a learning disability. Specific learning disability occurs more often than the other 12 categories. In the 2020-2021 school year—the most recent year for which there are data available—some 7.2 million children received special education services overall. Of these, 33 percent were for specific learning disabilities. How is it determined that a child has a specific learning disability? Each state must adopt criteria that are consistent with IDEA. Evaluators need to use more than a single assessment measure, and all instruments must be technically sound and administered by trained and knowledgeable personnel. The evaluation has to be “sufficiently comprehensive to identify all the child’s special education and related services needs.” In school districts, most educational evaluations are conducted by special educators and most psychological evaluations—generally comprising intelligence testing—are conducted by school or clinical psychologists. Depending on student needs, the evaluation team may also include other professionals, such as speech-language pathologists or occupational therapists. Independent evaluations are usually conducted by clinical psychologists, neuropsychologists, and/or educational specialists. Independent evaluators must be qualified, using the same or similar criteria as the school district, and they cannot be employed by the same district that the student attends. Although a psychologist can conduct a psycho-educational evaluation, in many cases the educational portion--and the resulting educational recommendations--tend to be sparse. In my opinion, students benefit from in-depth evaluations from a psychologist as well as an educational specialist who can then coordinate their findings to provide expertise from both their fields. It is important to be aware that a learning disability cannot appropriately be diagnosed without assessing learning. As stated earlier, to diagnose a learning disability the evaluator/s need to show that school performance is “adversely affected.” This may sound obvious, but unfortunately some professionals merely summarize what school personnel report and base their conclusions on what is at best second-hand data and at worst basically hearsay. Parents may wonder what evaluators look for to make this determination. First, the psychologist needs to rule out exclusionary causes of learning difficulties. For example, is there mental retardation? Serious emotional disturbance? The educational specialist needs to ascertain that the student has been exposed to appropriate instruction. She will also want to find out what services have already been provided in or out of school, and their duration, so that recommendations can build on these. There is no point in continuing to recommend services that have not helped. Next, the evaluators review the student’s educational history via verbal and written interviews with parents and teachers, obtaining information about the child from birth to the present to ascertain if any conditions or situations may bear on the current learning difficulties. Finally, the evaluators administer a set of statistically valid and reliable tests. Parents sometimes think that there is one test for dyslexia or any learning disability, but there is not. Instead, the evaluator pieces together many components to fully understand the student. For example, students with reading difficulty serious enough to be diagnosed as dyslexia also had difficulty learning letter names or sounds, or both, when they were younger, so the evaluator needs to find out when the learning issues began. A battery of tests, both standardized and informal, will help to provide a full picture about a child’s current levels of performance, areas of strength and difficulty, behaviors when presented with challenging tasks, and strategies that are used to meet those challenges. I like to think of all this as a puzzle that is pieced together until clarity emerges about how best to serve the student going forward. The period of time before Covid took over our lives and consciousnesses has been referred to as the Before Times. Therefore, it follows that we are now in the After Times. Covid is still a factor, albeit less so than it was before vaccines, and who knows when--or even if--that will ever change, especially as variants evolve. So we adjust as best we can.

I’m very, very fortunate to have been able to stay home for the most part and remain safe over the last 17+ months of the After Times. Thankfully no one close to me got Covid, but my heart breaks for everyone with a different experience. I am deeply grateful to the brave men and women who have been risking their lives to support the rest of us. However, I had to stop meeting with clients. Although I’ve occasionally completed reviews of students’ educational records over these last months because I could do that by computer, I’ve had to turn down requests to conduct evaluations. And I’ve so missed working directly with students and their families. Parents may wonder why when students have been back in classrooms with masks and social distancing, we couldn’t just do the same thing here in my home office. The dilemma for me has been that it’s essential that tests are administered reliably. (See this blog post.) In other words, they need to be given in exactly the same way as they were when the tests were normed. To be honest, I spent a lot of time trying to figure out if there was a way I could do that during the pandemic, but in the end I decided that there was not. As much as I try to make the evaluation experience comfortable and emotionally safe for children, the reality is that in the best of circumstances they are still usually anxious being tested, anxious especially on tasks that are difficult for them, and anxious about exposing their weaknesses to a stranger. That’s just the way it is. Given that situation, I believe that wearing masks might only exacerbate the anxiety, even assuming that mask-wearing alone would be enough protection for us both--a big assumption because there couldn’t be social distancing when we sit across a small testing table. I did wonder if perhaps children have become so accustomed to wearing masks now that it wouldn’t compromise test results. Obviously, there’s no way to know if that's true, but I believe that it could interfere, at least for some students. Moreover, it is often difficult to hear responses to test questions even without masks when anxiety or embarrassment, or both, can result in low voices and mumbling; masks could muffle their voices even more. Unfortunately, an examiner has to be able to hear the answers clearly because even a one letter-sound substitution can mean the difference between a correct or incorrect response. So I decided after all not to evaluate students. Until now. The good news is that vaccines are finally, finally available for ages 12 and up and hopefully for younger children by fall, so I’m looking forward to seeing families again soon. And I’m so very excited! This has been a difficult, scary, painful period of time for all of us, but there’s now light at the end of the tunnel as we slowly re-engage with the world. Welcome back everyone! I’ll be so happy to see you again. Please let me know how I can help.

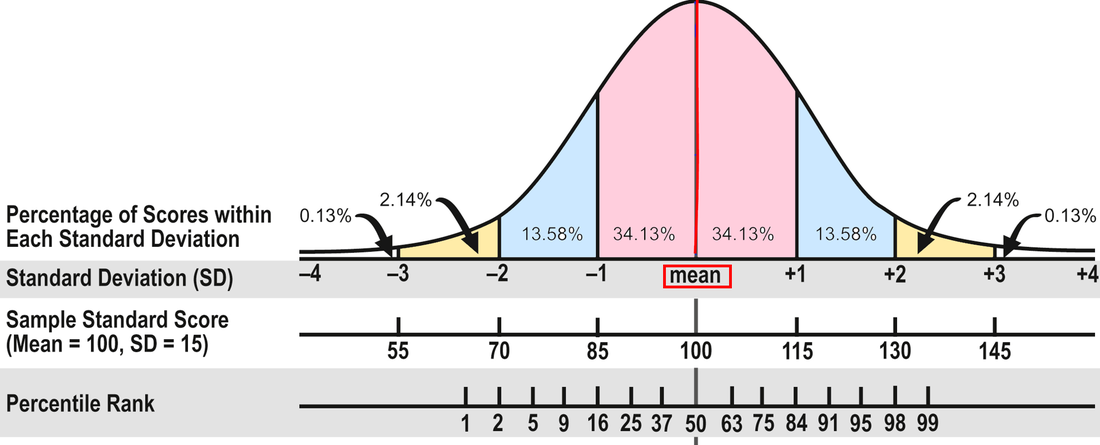

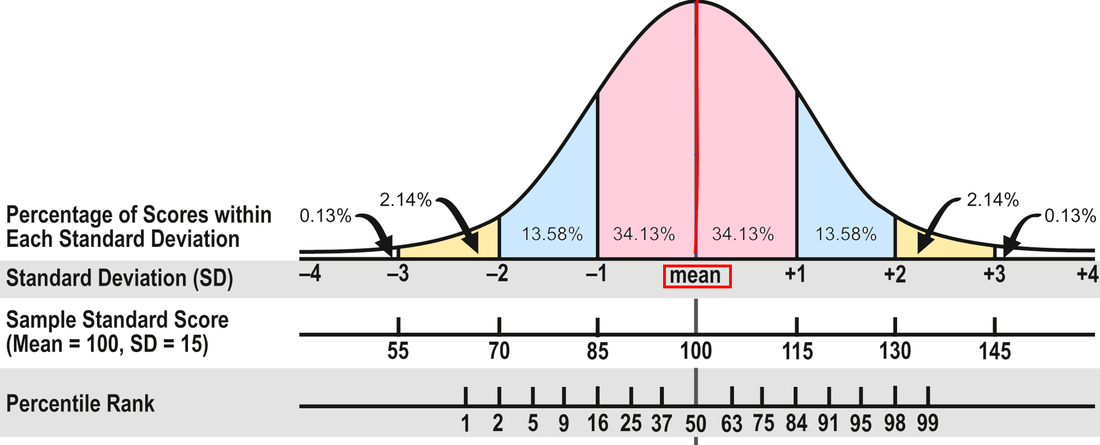

In Part 1, I wrote about the different kinds of test scores. In Part 2, I'll explain how to interpret those scores. As I said in Part 1, I prefer to use standard scores to gauge progress because they’re on an equal interval scale. But what do they mean? To assist with this discussion, consult the diagram below from Part 1:

The Average Range. To review, about 68 percent of the people who take a standardized test will obtain scores within plus or minus one standard deviation (explained in Part 1). The Wechsler and Stanford-Binet intelligence tests designate the middle 50 percent of the area between plus or minus one standard deviation as the Average range--or 90 to 109 for tests with a mean of 100 and standard deviation of 15. That's the area that many evaluators consider Average, including me. In other words, half the students taking the test will have scores within the Average range and half will have scores that are above or below Average.

However, some researchers and clinicians consider the full 68 percent to be in the Average range, or scores between 85 and 115. Neither interpretation is right or wrong because there isn't agreement in the field. In my opinion, it makes more sense to use the 50 percent figure; it doesn't seem to me that the scores of almost two-thirds of the population are in the Average range. If 90 to 109 is Average, 80 to 89 is Below Average and 110 to 119 is Above Average. (FYI, psychologists use the terms Low Average and High Average for Below and Above Average.) It might help you keep track if you make a simple chart of these scores. For example:

Confidence Bands. Moving on from the scores themselves, have you heard people talk about confidence bands? That's an important concept to understand because a single testing may not demonstrate a student's true score, his or her actual ability. The true score is a statistical concept and too complicated to explain here, but the point to understand is that there is some error, some uncertainty, in all testing--in the test itself, in the testing conditions, in the student's performance, and so on. To account for this uncertainty, a confidence band is constructed to indicate the region in which a student's true score probably falls. Evaluators can select different levels of confidence for the bands; I use 90 percent. Therefore, I provide a confidence band that indicates the region in which a student's true score probably falls 90 times out of 100. Test publishers usually compute these for users.

Here's an example. Mary obtained a standard score of 97 on a reading test, which is solidly in the Average range (90 to 109). However, although the obtained score on a test gives the best single estimate of a student's ability, a single testing may not necessarily demonstrate the true score. Mary's standard score confidence band is 91 to 104. Subtests and Scaled Scores. Many tests measure different parts of a domain with component tests called subtests. Sometimes the subtests yield scaled scores, which are standard scores that range from 1 to 19 points with a mean of 10 and a standard deviation of 3. Scaled scores between 8 and 12 are considered Average. Composite Scores. Subtest scores may stand alone if they have high statistical reliability. If not, they should only be reported as part of a composite score. A composite score is computed by combining related subtests--for example, subtests that assess word recognition and reading comprehension or math computation and applications. Because composite scores are generally more statistically reliable than subtest scores, they are sometimes the only score that should be considered. However, it is better to use tests with highly reliable subtests when they are available because composite scores can mask the differences among the subtest scores. For example, Richard obtained these subtest scores on a recent reading test: Word Recognition, 73; Pseudoword Decoding, 78; and Reading Comprehension, 107. The 73 and 78 scores were in the Borderline range (70-79), and the 107 was in the Average range. The composite score was 82, in the Below Average range. However, none of the three subtests was Below Average. Because of the variability between the word recognition and decoding scores on the one hand and the comprehension score on the other, it would have been more accurate to not provide a composite score in this case. Here's another example. Nalia obtained two math scores recently: 100 in Math Applications (Average range) and 84 in Math Computation (Below Average) with a composite score of 90, which is at the bottom of the Average range. However, there was a 16-point difference between the two subtest scores, and it would be incorrect to say that Nalia's math performance was in the Average range when she was struggling with computation. Yet sometimes this kind of difference isn't explained in an evaluation report, so you'll need to read carefully and critically. I've presented quite a bit of technical information in this blog post. Please let me know in the Comments below if you have any questions! And feel free to share any ideas you have for future posts. In Part 1, I discuss the different kinds of test scores and what they mean and don't mean. In Part 2, I'll address how to interpret scores--what's considered average, confidence bands, the differences between composite and subtest scores, and so on. The array of test scores in an evaluation report can be confusing. On standardized tests, the number correct is called the raw score. A raw score by itself is meaningless because it’s not the percentage correct; it’s just the number correct, and different tests have a different number of items. So publishers convert the raw scores into derived scores to compare a student’s performance to that of other students his age in the norm group—the people the test was standardized on. There are several kinds of derived scores. Before I discuss a few of them, I need to introduce some statistics. I know this is technical, but bear with me because it will help in the end! Most psychological and educational test results fall within the normal or bell shaped curve. The normal curve is divided into standard deviations that measure the distance from the mean (the average score). In the diagram below, you can see that about 68 percent of the population will have scores between plus and minus one standard deviation (pink area). An additional 27 percent will have scores between plus/minus two standard deviations (about 95 percent; pink and blue areas). And 4 percent more will have scores between plus/minus three standard deviations (about 99 percent; pink, blue, and yellow areas). Now pat yourself on the back for getting through this section!

I worry a lot about the difficulties of administering standardized tests. That might sound a little strange, but assessment data are essential to my work with children, and it concerns me when tests are invalidated, usually by mistake. A standardized test compares a student to a "norm," or the average performance of similar students, generally in a national sample. Part of the process of producing such a test involves "norming," or administering it to a sample of children considered representative of the national population. During norming, the test is administered under specific conditions with very specific instructions to the students in the normative group, and the publishers expect users to later replicate those same conditions and use those same instructions. Otherwise, the results are invalid. It's as simple as that. If test administrators allow extra time or ask leading questions that are not in the test manual or give students advanced preparation or permit multiple attempts beyond those allowed or in many other ways give students advantages that the children in the normative sample did not have--or conversely make the test more difficult--they are invalidating the test results. I often need to read other professionals' evaluation reports, and sometimes the test scores appear to be an extreme over-estimate of the student's ability. I can only guess at the reasons for this because there's no way to know what occurred during test administration. Still, it makes me wonder how carefully the tests were administered. Admittedly this can be confusing because tests can have different administration and scoring rules even when they measure the same task. For example, some oral reading tests count all self-corrected errors, whereas others suggest that we note these corrections but do not count them in the scoring. Some tests have time limits per item administered and some do not. And so on. Yet while this is indeed confusing, it is also the evaluator's responsibility to understand and apply the rules appropriately. I frequently review the test manuals before giving some tests even though I've administered them dozens of times. I just consider it part of the job. But there are other ways to invalidate a standardized test. Some evaluators' reports provide examples of items that students answered incorrectly. At first glance this might seem to make sense; after all, it can be part of an in-depth error analysis. The problem is that this practice can weaken the security and integrity of the test items. I sometimes describe the type of item with sample words that are not part of the actual tests. However, when real test items are shared, there is the possibility that they will become known by teachers or parents, or both, and ultimately by students, which invalidates the test. Parents or teachers may even see these errors and teach them to students--which makes the test useless for re-evaluation at a future time. If the items are directly instructed to a class, this test can be invalidated for all the students in that class. Now you may assume that in the course of a school year, some of these items would naturally be part of the curriculum anyway, and you are certainly correct. Tests are meant to sample the entire domain, e.g., of word meanings or high-frequency words or spelling. But inadvertently teaching some of the items is not the same thing as purposely teaching specific test items. Ultimately what's important here is to carefully guard standardized tests so they can remain useful indicators of student performance. While I believe that informal tests that have not been standardized are also useful, and I include them in my test battery, there's no substitute for good norm-referenced tests. We use standardized tests to compare students to similar students in the national sample; informal tests can flesh out that information to inform instruction. Both are necessary sources of data. You may have heard the term phonemic awareness but perhaps you’ve confused it with phonics. Or you know that it’s not phonics, but you’re not really sure exactly what it is! Phonemic awareness is a big name for a very small part of the reading process, and yet it happens to be crucial to learning to read. Phonemic awareness is the understanding that words are made up of separate sounds—and the ability to manipulate those sounds in various ways. Big deal, you might say. Can’t everyone do that? As it turns out, they can’t. Most children start school able to discriminate letter sounds, called phonemes, e.g., mat versus man. However, that discrimination isn’t necessarily at a conscious level. Research has shown that we hear a syllable as one acoustic unit, but we need to break it down into individual segments to analyze it. The catch is that we have to learn how to do this. It doesn’t happen naturally. And as with all learning, some children find this easier than others. You might wonder why phonemic awareness is so important. Here’s why: It's essential for reading success. It enables children to benefit from phonics instruction, and being able to sound out words is the most important clue to identifying them. Context can help confirm that a word has been sounded out correctly, but it isn’t efficient as a first clue. There are many different phonemic awareness tasks, such as rhyming, isolating a sound from a word, blending letter sounds into words, segmenting the sounds, or moving sounds around by adding, deleting, or substituting them. Some of these tasks are relatively easy and some not so much. For example, in a blending task, a child might be asked what word /s/ /a/ /t/ is (sat). A deletion task, also known as elision, requires a student to take away the /k/ sound in clap and say that lap is the word that’s left. A substitution task might require a student to take away the /s/ sound in side and replace it with a /t/ sound so that side becomes tide. Incidentally, phonemic awareness isn’t phonics. Phonics instruction teaches children which letters are associated with which phonemes and why. You’ll often hear phonics referred to as decoding—and that readers who understand and can apply the relationship between letters and sounds can “break” the code. Pretty cool, don’t you think? Breaking the code is empowering to new readers. Can you sound out these nonsense words? clag spanthet Of course, you’re able to apply your knowledge of letter-sound correspondences and the rules that govern them because you’re a skilled reader and can do this automatically. We want children to be able to do this automatically too whenever they encounter words in print that they’ve never seen before. If they struggle with decoding, their cognitive resources are diverted from the demands of comprehension. Getting back to phonemic awareness, it's fortunate that many children can acquire this skill from activities at home before they even enter kindergarten, and these can be presented in a fun way. For example, parents can encourage awareness of sounds within words by reading and reciting nursery or other rhymes aloud and inviting children to create their own. There are also many children’s books that emphasize rhyme, alliteration, or assonance. Similarly, children can play rhyming or alliteration games or repeat or create tongue twisters. Or they can clap or tap out each syllable in a word, make up sentences that contain words that start (or end) with a particular sound, or play with language in myriad ways. I’m always pleased when I hear young children spontaneously making up words that rhyme or start with the same letter, such as mitten kitten sitten shmitten. Or p-p-p-p-Peter. Not all children will acquire phonemic awareness from these informal activities at home. Some will need direct instruction in the classroom. But while it’s preferable for this to occur in kindergarten or first grade, phonemic awareness can also be successfully taught to older students. I’d love to hear about your experiences with this important topic! Educators don't agree about the value of teaching cursive writing to children. While the research is clear that writing by hand activates different parts of the brain than typing does, aids memory, promotes the development of fine motor skills, and possibly helps in learning to read, it is less clear about whether children should learn manuscript versus cursive writing, or both. Instruction in cursive writing is not part of the Common Core State Standards, and many states no longer require it in the curriculum. While we're on the subject of handwriting, I want to say that I reject the argument that in this digital age children don't need to write by hand period and that the less time spent on handwriting instruction the better. I disagree with that idea in the same way that I disagree with the premise that children don't need to learn basic mathematical operations because calculators can do it for them. I truly LOVE my computer and my smartphone, but the reality is that keyboards, smartphones, and calculators are not always available. Nor should they always be available. If I'm baking cookies and want to make one-and-a-half times the amount in the recipe, I should be able to compute that without grabbing a calculator! If I'm making a shopping list or writing a short note to my postal carrier, I should also be able to do that without a keyboard and printer! Anyway, that small rant aside, the focus of this blog post is cursive writing and not handwriting per se. Those who disagree with teaching cursive believe that the instructional time can be better used, to teach computer skills, for example. I believe that it's essential to teach computer skills, but there are also several arguments that support the teaching of cursive writing. Many people think that cursive is faster than manuscript writing because the pencil stays on the page between letters. This is important during certain tasks--for instance, taking notes during a lecture or completing an essay exam. Another argument in favor of cursive is that we need it to read historical documents in their original form, such as the Declaration of Independence or diaries of famous people. Is this an everyday occurrence? No, of course it's not, and yet, the reading of original sources enlivens and enriches content area lessons. Still another argument is that without cursive we would have no way to provide a signature when required to both sign and print our names, such as when receiving a registered letter at the post office, applying for a loan, or signing a will. Moreover, it seems to be easier to forge a printed signature. I support the teaching of cursive. It does require precious instructional time to teach it and then to practice it, but I believe that it's worth the time. It's part of what marks an educated person. And as the hand, eye, and brain coordinate the effort of forming cursive letters and connecting them into words, the process requires concentration, attention to detail, and planning--all of which are essential to learning in general. Furthermore, when taught well, with an emphasis on correct posture, the position of the paper, and an appropriate pencil grip, and when letters with similar forms, or families, are taught at the same time, most children enjoy the process. To children, writing in cursive is part of being grown up, and they are proud of their accomplishments. Some 21 states now require this instruction, and I hope that others follow suit soon. What are your thoughts? Parents usually suspect that their child has a learning problem, but they don’t always know what to do about it. They often begin by scheduling a conversation with their child’s teacher. Unfortunately, school personnel frequently say that students are doing fine or perhaps that they just need more time to develop. This creates a dilemma for parents; should they override the advice and possibly upset the teacher or just wait and see what happens? Parents want to trust that school professionals know best. The problem is that many times children aren’t doing fine and waiting and seeing rarely has a positive outcome. People don’t grow out of learning disabilities. In fact, the sooner the problem is addressed, the easier it is to help students catch up to their peers. If you suspect a learning problem, it is generally advisable to have your child evaluated. Sometimes parents worry that professionals will label their child and that the label will then become part of the permanent record. While it is true that labels can “stick,” it is also true that confirming what you already suspect, hearing the words spelled out for you, can be a tremendous relief. Parents have told me that many times over the years. Now at last the problems can be addressed with correct school placement, instruction, or accommodations—and sometimes all of these! You might begin by requesting that school district personnel conduct educational and psychological evaluations, or you could have independent evaluators do it. Either way, consider the results and recommendations with a critical eye. Do they support what you’ve been thinking? Does the report suggest detailed ways to help? If the answer to these questions is yes, then that’s terrific! You’re all set. Congratulations for doing this for your child. But maybe after all the waiting and preparation, the testing and report, you find that what you’re reading or being told is a complete surprise. Does it seem too good to be true? Can all the difficulties you’ve noticed really just be in your imagination? There are two possibilities here. On the one hand, perhaps you’ve exaggerated the school difficulties and everything is okay after all. In that case, you can take a breath and relax. But conversely, maybe the evaluator hasn’t dug deeply enough. While hearing that all is well might make you feel better in the short term, it will be small comfort if the problems persist or get worse. I’m so sorry if this is what happened, but it is not uncommon. Sadly, those are often the kinds of cases that are referred to me. So what is a parent to do? The best advice I can give is that if the first opinion doesn’t adequately address your concerns or answer all your questions, ask for a second opinion—an independent evaluation. Then get recommendations from people whom you trust, preferably professionals with experience serving children with learning differences. And carefully research the credentials and experience of the person you choose. Just as in any field, the strengths of evaluators vary. Good luck on this journey to help your child. Please let me know if I can help you. Sometimes I wish we could eliminate special education. Every child has strengths and weaknesses, and the goal of education is to meet all of their learning needs; it seems unnecessary to place some students in a separate category that requires more “special” education than others. The problem with that logic is that before we had special education, before Public Law 94-142—the Education for All Handicapped Children Act (now the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act [IDEA])—was passed in 1975, more than a million children with disabilities were completely excluded from the education system, and many more had only partial access. The Federal Government did not require schools to include children with disabilities, so children that schools deemed uneducable could not attend public schools. Some families were able to send their children to specialized private schools and other children were institutionalized. A great many others had no option but to stay home. Those who were enrolled in public schools were generally either placed in regular classrooms without accommodations or segregated in special classes. P.L. 94-142 guaranteed a free and appropriate education for all children—with due process protection—and that was a big deal. Moreover, the law stipulated that children who received special education services had to be placed in the “least restrictive environment” so they could be educated with other children as much as possible, and states were required to provide a continuum of such placements—a range of placements from the regular education classroom to hospitals or institutions. But P.L. 94-142 was first implemented over 40 years ago. Do we still need it? Unfortunately we do. If all students were placed in the least restrictive environment, receiving instruction that was appropriate to meet their needs, parents would not ask me to conduct independent evaluations. They would not require due process hearings to settle disputes. And it would not be necessary to attend team meetings in which outside experts like me advocate for better placements and services. I would truly like to believe that all children can receive the kind of education that helps them reach their potential without the need for legislation—that we can manage without IDEA. Perhaps we’ll get there someday, but we’re just not there yet. |

AuthorDr. Andrea Winokur Kotula is an educational consultant for families, advocates, attorneys, schools, and hospitals. She has conducted hundreds of comprehensive educational evaluations for children, adolescents, and adults. |